In July 2011, I was working in a hospital in Mwanza, a city in northern Tanzania — I was a fourth year medical student on a short elective placement, taking a period of time to experience healthcare in another country before my final year started and with it finals and job applications. In my brief time in Tanzania, I fell in love with it; with its land and people and culture; and in return it taught me a huge amount about a world wider than I’d known existed, and about my own privilege and the things I’d been taking for granted for the past two and a half decades.

On my last day, my supervising consultant asked me about how healthcare works in the UK. I explained it to him in, more or less, the words of the leaflet that was sent to all UK households in the lead up to July 5th 1948:

“It will provide you with all medical, dental, and nursing care. Everyone — rich or poor; man, woman or child — can use it or any part of it. There are no charges, except for a few special items. There are no insurance qualifications. But it is not a “charity”. You are all paying for it, mainly as tax payers, and it will relieve your money worries in time of illness.”

He asked a few questions about how it worked, about how the tax system worked, about what happened to the young and the retired and the sick and the unemployed. I tried to answer his questions. I quoted the principle that those of us who champion the National Health Service hold to be true: the principle of a system of universal healthcare, delivered free at the point of need.

He said with a kind of wonder: “But that’s a marvellous thing.”

*

It is a marvellous thing.

The NHS is a marvellous thing that until that point, that day, I had been absolutely sure of and had taken absolutely for granted, like the sun coming up.

And today it celebrates its seventieth birthday.

There’s been a cultural shift in the years since I returned home that summer, seven years ago. The shift of government to be meaner, less welcoming, more inward looking. The elevation of voices that are hostile to evidence and expertise, and the collateral silencing of experts and professionals. The consequences of austerity. There was a time in my adult life when I never thought I’d have to fight for the NHS. There are days now when that seems as if it was an awfully long time ago.

I have had reason to be grateful for the National Health Service for many years — among other things, I am the daughter who only ever had a father because of a kidney transplant performed by the NHS and the child who is alive because of maternal and neonatal services provided by the NHS. But my reality is also that as an adult, I have experienced the NHS almost entirely as a doctor who lives her life at the coalface of medicine.

That changed earlier this year.

There is a story to be told here. It is a story that has been told in waiting rooms and during difficult phone calls and alluded to piecemeal on social media. It is a story that I’ve been needing to tell in its fullness, and today seems the time to tell it.

This is the story of my mum’s death.

And it is also the story of how I ended up in the cafeteria of a strange hospital late at night, thanking God and Nye Bevan for the bold and miraculous hope of a system of healthcare for everyone, paid for by everyone, and delivered free at the point of need.

*

On January 31st, 2018, my mum celebrated her sixtieth birthday. It was a Wednesday. I was at work. I’d sent her a card and flowers. I checked my emails at lunchtime, and had one from her letting me know the five person dinner she had planned for that weekend had grown somewhat in the planning of it and that I should plan to make chicken curry for twenty people. I rolled my eyes and sent her a shopping list (“chicken breasts — enough for hungry people”). I arrived in Newcastle that Friday evening, and we had a nice evening and a nice Saturday together, watching television and fantasy house shopping on the Internet and preparing food. For once, we managed not to have a row about anything.

A few hours before her guests started to arrive, she started to feel breathless. She had had asthma for most of her adult life, and had had a bad winter of coughs, colds, and chest infections, but had been well for the last week or so, better than she’d felt in months. She was adamant that she didn’t need to see an out of hours GP or go to the emergency department — after all, people were coming. She would use her inhalers and have a lie down and be fine.

She wasn’t fine.

It eventually became clear even to her that her salbutamol inhaler wasn’t going to do the job this time, but by that time she had become so short of breath she wasn’t able to speak more than a few words and she wasn’t able to stand up on her own. And, of course, by that time, her living room was full of people. As I was dialling 999, she was still trying to find the breath to ask her sister if she was sure it was okay for her to go to hospital when there were all these people in the house expecting food and a party.

Paramedics from the North East Ambulance Service arrived with lights and sirens, and for a little while it seemed as if it all might settle down with a nebuliser and some oxygen. My memories of the next few minutes are incoherent and are in flashes: from her oxygen levels starting to climb, to her being on the floor with her head between my knees so I could help manage her airway until extra hands arrived, to another four paramedics thundering up the stairs, to us being kicked out of the room, to the moment when I heard someone say that they had lost cardiac output.

And that was when I was unwillingly thrust into a role that I’d never prepared for: being someone whose role in the massive machinery that makes up the NHS was to be not the doctor. The last time I had been at work, which at this point seemed like a lifetime ago but was in reality only two days earlier, I had been the cardiac arrest team leader. Now, I was the relative. I was the person panicking on the other side of a wall, waiting, waiting, waiting, with my aunt and my stepsister and my mum’s husband, and I was listening to someone else run my mum’s cardiac arrest in the next room. I had sent a text message to my family back in Glasgow when I’d left the room, which meant I had a timestamp, and, let me tell you, when you’re a healthcare professional who’s listening to someone else do CPR on someone you love, a timestamp is the worst imaginable thing to have. Because I knew when it had been twenty minutes, and when it had been thirty minutes, and when it had been forty minutes. And I can’t turn off the part of my brain that knows what it means when someone hasn’t had a cardiac output for forty minutes, even if they have had the best possible quality CPR anyone could ever have had. There were nine paramedics and a doctor in the house by that time, not counting me. I couldn’t turn that part of my brain off even when that someone was my mum.

When they got her back. When they carried her down the stairs of the house I grew up in. When we all breathed again, for a few minutes. The thing I remember about it was that the first paramedic came back, to make sure that all their mess had been cleared up and that we wouldn’t come home to find syringes or Guedels on the floor. And when I tried to thank her, she said to me, “It isn’t over yet.”

My mum had exemplary care after she left her house that night. She was taken to the resuscitation room in the emergency department, and then almost immediately to the intensive care unit. My family and I were told exactly what was happening. I don’t think any of us slept when we left the hospital, but I don’t think any of us doubted that she was being left in safe hands and given world-class healthcare.

The days that followed that night were some of the longest of all our lives, but we never had reason to doubt that.

The life of an ICU visitor is a strange one; it exists in its own part of the time-space continuum. I had never spent any significant time in a high dependency area of a hospital in a context that didn’t involve me carrying three bleeps and a jobs list the length of my arm. It turns out that for other people, time in those parts of a hospital is about waiting, and watching, and wondering. It was about all my family — my family of origin, the ones who had already been there, and my other family, the ones who’d dropped everything to drive to me from Scotland when they got that first text message — camped out in a corner of the waiting room, telling stories and drinking too much hospital coffee and waiting for news. It was about sitting on my hands so that I would stop trying to react every time something bleeped, and getting to know all of the nurses, and trying not to think too hard about what I thought I already knew.

We waited for four days.

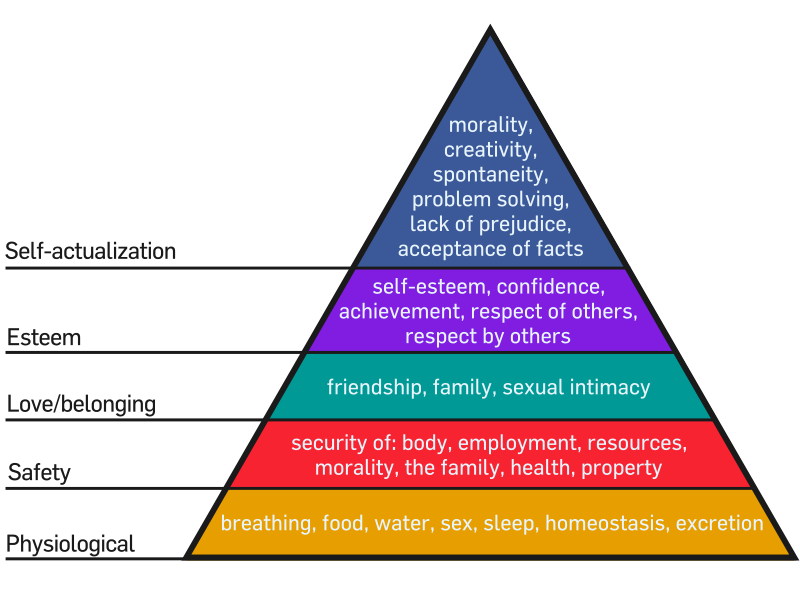

Do you have any idea how much an intensive care bed costs for four days?

At the end of the fourth day, we were given the results of the investigations she had had to determine how much of her brain function had survived when she had had an out of hospital cardiac arrest on her bedroom floor.

The answer was: not much, not enough to be taken off a ventilator, not enough for her to ever have anything like a meaningful recovery.

It’s like I said. I hadn’t been able to turn off the part of my brain that knew what it meant when someone hadn’t had a cardiac output for forty minutes. Not even when that someone was my mum. Maybe especially because that someone was my mum.

In the next 24 hours, she had some of the highest quality palliative care I’ve ever had the privilege of witnessing. She had time for everyone who loved her to come and see her, to say the things they needed to say. I spent part of that time telling her that I wasn’t sorry about the times we had argued; just because she was dying didn’t mean she hadn’t been wrong all those times. She would have expected nothing less of me. As a family we asked to explore the possibility of organ donation; something that ultimately wasn’t possible but that the transplant coordinators did their best to facilitate for us and for her. She was comfortable and looked after, and there was nothing that was too much trouble for the nursing or medical staff. In the dark hours before dawn, I remember being brought a cup of coffee by Sister and her apologising that it was too strong. “Don’t you dare apologise, it’s 5am, it’s fantastic,” I said.

My mum died a little after lunchtime on Friday 9th February, peacefully, with dignity, surrounded by the people she had loved.

*

I have a lot of memories of the week before she died. I’ve written here about only some of them.

One of the things I remember most clearly is from just 24 hours after she was admitted to hospital. I was sitting in the hospital canteen. I was alone for a few minutes. My memory is in some ways the answer to that question about knowing how much an intensive care bed costs for four days, because the answer is that I don’t know, and that I still don’t know.

My mum had the best possible chance at life and the best possible death, and all the way through she had access to the best healthcare in the world.

It was free at the point of her need, just as it had been for her whole life. We have been charged no money for the care she had. We will never be sent a bill or expected to write a cheque.

That moment in the canteen of the Royal Victoria Infirmary was when I thanked God and Nye Bevan for the bold and miraculous reality of the NHS.

*

On July 5th 1948, the Secretary of State for Health visited what is now Trafford General Hospital and met the first patient of the National Health Service, a thirteen-year-old girl called Sylvia Diggory. Later, she said, “Mr Bevan asked me if I understood the significance of the occasion and told me that it was a milestone in history — the most civilised step any country had ever taken.”

It isn’t perfect. There are things that we can do better. There are always things we can do better. There are things that go wrong, and those things should be taken seriously. There are days when working in it the whole enterprise feels as if it’s held together with a piece of string, the power of cake, and the goodwill of its one and a half million employees.

In spite of that, I still believe that it can be everything that Attlee and Bevan wanted it to be; that it is an aspirational thing that at its best represents the best of us.

And it is worth me saying this:

That my mother and I agreed on nothing, politically, but this, this we agreed on.

I work for the NHS. I will always work to make it better, to make it into the best possible version of itself, and I will always work against the unscrupulous and uncaring whose only goals are devaluation and privatisation.

But today the National Health Service celebrates its seventieth birthday, and all I am today is grateful for everything it stands for and for that week when it was a very real light in the most terrible darkness.

It is a marvellous thing.

It is a miracle.

And it can and should be the very best of us.