All over the UK, newly graduated medical students are starting to look ahead to the first Wednesday in August and their first day as Actual Proper Doctors.

If they are anything like I was, they’ll be having increasingly terrifying nightmares about holding the cardiac arrest bleep on their first night. And getting lost. And they’re the only one on the arrest team. And they can’t remember how to do CPR. And there’s a dragon in the corridor. No? Just me? OK.

A couple of years ago, I wrote a long piece that contained practical advice for new doctors. If you are a new doctor and you are looking for bullet points on where to get help, how to ePortfolio, the unsettling but central role that half-coloured in ticky boxes will come to play in your life, and other things, that piece is here and still contains the best advice I have to give. Over on Twitter, search the #tipsfornewdocs hashtag, and remember that we all remember this and that almost none of us bite.

Today, I want to talk about something a little bit different. I want to take a bit of time to think about resilience and self care.

The idea of ‘resilience’ is a psychological one that has to do with the capacity of the collective and of the individual for what I’ll call ‘coping’. It was defined by Andrea Ovans in the Harvard Business Review as “the ability to recover from setbacks, adapt well to change, and keep going in the face of adversity”. In the last few years, it’s developed into a buzzword in the language used to talk about and to public sector workers. The first time I became aware of it as a thing that was being said to doctors was during the junior doctor contract negotiations in 2015.

Now, the first thing to say is that I’ve never met a junior doctor who didn’t possess resilience. It is a requirement of the job. It is a requirement of getting the job. So, the second thing to say is that when the government talks about junior doctors not having resilience, they are lying.

But if what they mean is that junior doctors have proven increasingly unwilling to be actual martyrs — well, yes, that might be true, and that might also not be a bad thing.

As a teenager, I wanted to be John Carter from ER. I wanted to live all the hours in the day for my job. There is a picture of a recruitment poster for Emergency Medicine going around at the moment that invites applicants to “choose surviving on coffee and adrenaline”. It is a terrible message to send, but half my life ago it was absolutely what I wanted for myself. And even as a slightly more elderly medical SHO, there are days when that kind of thinking still has its seductive qualities. On the seventh day in a row of thirteen hour days, I can enter a mental state that is some sort of meld of beautifully Zen and utterly psychotic. I know all my patients inside out and back to front, and half the patients of the other teams, too, and I am completely on it and, look, I just live here now and I’m pretty sure that’s actually fine. (I have a bad-coffee-and-sleep-deprivation-fuelled memory of this precise thought process going through my brain, about eighteen months ago, and also I think I was skipping down a corridor at the time.)

It is perfectly possible to live like this for short periods of time. I clearly do and so do lots of other people, not all of whom are doctors. It is not sustainable. A period of work like that has to be punctuated by a period of rest and rejuvenation, or else the whole thing falls apart. I love my job, but my capacity to do it for thirteen hours a day without a day off is not infinite. I believe that that is true of any human in any job, no matter how much they might love it.

It is partly because no one has an infinite mental or physical capacity. In this job, that part of it is a patient safety issue as much as it’s anything.

It is also partly because you do eventually go home from your job, and it is at that point that you remember there is no food in the fridge and that you have no clean pants.

And that’s the part we don’t hear about enough when we hear about resilience. We don’t hear about self care: about how to keep ourselves alive and fed and sane and happy. In fact, we too often hear the opposite of that: that to do the things we need to do to take care of ourselves is selfish or lazy or uncommitted or in some way not being a team player. That is a perception that I want to challenge.

*

First, put on your own oxygen mask.

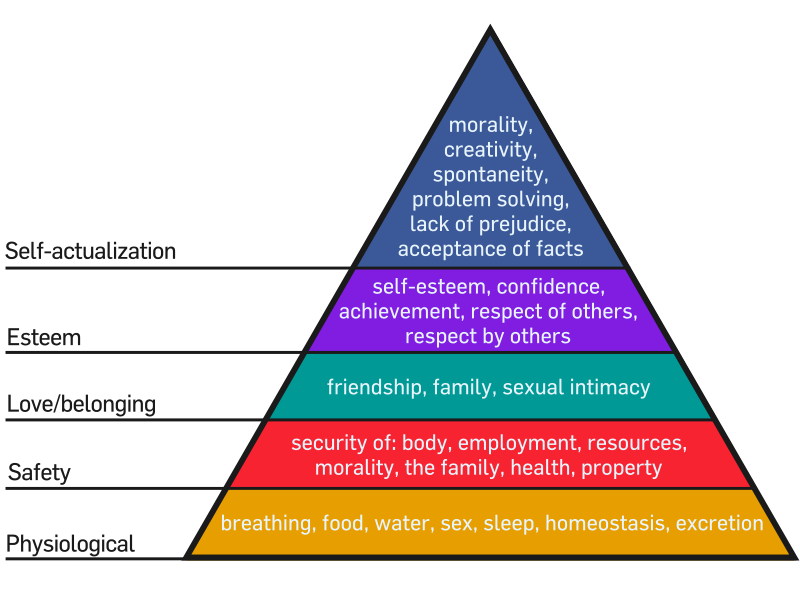

Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs. (Wikimedia Commons)

There are lots of ways to look after yourself well, and I can only talk about what works for me and what hasn’t worked for me. This is the part that is non-negotiable. You need to eat. You need to drink. You need to sleep. You need to put on your own oxygen mask first. You need to remember to go to the toilet.

I am pretty sure that if anyone had said any of that to me in the week before I started FY1, I would have rolled my eyes too. I was worried I might accidentally kill someone, not that I might forget to pee. Trust me, you will forget to pee.

The need to eat and drink and sleep is about more than keeping yourself alive. It is about that, too, of course, but it’s also because everything seems so much worse when you haven’t.

This is a crap job, sometimes — for all sorts of reasons. A tip of the hat to @DrTonyGilbert on Twitter who aptly described this as “those nights where you’ve been punched and your shoes are full of ascites and you think, ‘I could’ve worked in a bank'”. The world will be much more manageable on the other side of a good meal and eight solid hours of sleep. I’m not saying those things will fix everything, but they will make most things look a lot less dire.

So:

- FY1s cannot live on coffee and Mars bars alone.

- Eat breakfast. You don’t know when you’ll next get a chance to eat.

- But do eat lunch. There are really very few things that can’t wait until you’ve eaten a sandwich and had a drink.

- If you can get off the ward for a break to eat lunch, do that. The days when you eat with a sandwich in one hand while writing a discharge letter with the other hand will come, but they should be the exception rather than the rule.

- Drink. If your patients’ kidneys need fluid, so do yours. The correct response to, “Doctor, Mrs Jones has only passed 30 mls of urine in the last 3 hours,” should not be, “Well, that’s more than I have.” Get a reusable water bottle and use it.

- Meal plan. If you can make food with leftovers, you can come home from an on call shift and have a home-cooked meal in the time it takes to transfer a plate from the fridge to the microwave. This is a wonderful thing. It also means that you’re less likely to collapse on your bed and fall asleep without eating.

- The existence of supermarkets that will provide you with ready-prepared food and people who will bring delivery food to your house is evidence of the kingdom of heaven on Earth. It isn’t sensible to live off them, perhaps, but they have their uses.

- Comfy shoes. Get some.

- Take care of your physical health. Register with a GP. If you are a doctor with a chronic illness or a physical disability, take the time you need to take care of that. A friend of mine, Dr Beth (no, we are not the same person), wrote a blog post recently about this which was aimed particularly at doctors who have diabetes but which I think is worth reading for everyone.

Learn how to say no.

Take your days off. Take your annual leave. If your work emails are connected to your phone, learn how to unsync them.

There will always be situations where someone needs a shift to be covered on short notice. People get sick. People have family emergencies. Rota coordinators fail to take into account the fact that the staff grade’s contract was only for six months and ended last week. You will end up being the person who covers these shifts some of the time. You do not have to be the person who covers these shifts all of the time.

At some point, you will be asked to participate in rota monitoring, where you fill in a form for a couple of weeks with your rota hours compared with your actual hours. Your Trust is supposed to use this to ensure that your rota is legal, that your department is staffed appropriately, and that you are being paid correctly. If you are asked to work differently to your usual practice or you are asked to lie about your hours, say no to this too. (However, do not expect the person from the rota monitoring department to understand your job. I gave up fighting that battle on the day one of them tried to insist that I should be leaving the cardiac arrest bleep behind when I went to eat lunch.)

Likewise, there will always be work that needs to be done outside of normal work time. This will sometimes be valuable, and sometimes not. Like the online induction module that even as I type I am side-eyeing in my learnPro account, which will take time that I could instead have spent learning something about cardiology before I commence my six month cardiology rotation. The point is, there are exams, and ePortfolio, and quality improvement projects, and things to read and learn. This isn’t entirely a bad thing. It is part of what being a professional is. But develop some sort of system to deal with it so that it doesn’t end up taking over your whole life, because it absolutely will if you allow it to.

Don’t forget to look after your mental health, too.

There are lots and lots of doctors who have mental illness. It is not a shameful thing. It is not an unusual thing. Don’t ever let anyone tell you otherwise. You will not be the only doctor who takes medication to maintain your mental health, or sees a counsellor or a psychiatrist or goes to therapy. Do what you need to do to keep well, just the way you do for your physical health.

If the above does not apply to you, don’t presume it never could and don’t ever be ashamed to ask for help.

My sanity has been saved — so many times and in so many ways — by having brilliant friends.

If you are struggling, please talk to someone.

If you think you aren’t struggling, please talk to someone anyway.

Your most readily available resource is your colleagues. You may not have met your fellow new FY1s, yet, but you will become each others’ most reliable support. (The thing about getting off the ward for lunch if you can? It’s even better if you can get lunch together.) There is no one who understands this weird job like the people who are going through it with you. Use your seniors. Your educational supervisor is there to support you, not just to tick boxes on your ePortfolio. If they aren’t supportive or you think they’d be difficult to talk to, there are other consultants. If that seems too intimidating, your regs and SHOs did this not too long ago and I promise most of us are nice. The administrative staff, too. In my FY1 year, it was known that our postgraduate administrator’s office door was always open for a cup of tea and a biscuit and a bit of a cry and I think we all took her up on that at least once.

You won’t be the first person to have cried in a sluice; that’s what sluices are there for. If you cry in the sluice every day, that’s not okay and please talk to someone.

It is okay to not be okay, but people won’t know you need help unless you tell them.

Do the things that make you happy.

I suppose there is a professional bit to this, about finding your niche and finding your people and not worrying when you don’t like every single rotation you do as an FY1 or even FY2. I’m pretty sure that I grew up thinking it was all “being a doctor” and I know that I have friends and family who pretty much still think it’s all “being a doctor”, but one of the brilliant things about medicine is that it’s all so very different. I think that’s all true, and you’ll do that.

But what I really wanted to say was, remember that you’re still a person as well as a doctor.

I can’t tell you what it is that makes you happy.

The things that make me happy include but are not limited to:

- Real books

- Sunday dinner with people I love

- Running around the parks of Glasgow or along the Clyde with music or a podcast and the sound of my feet on the tarmac

- The work I do in “my” cathedral

- Taking the extra five minutes in the morning to make real coffee

- Cats who like to give me Eskimo kisses

- A knotty bit of Beethoven and the adrenaline rush from singing it on stage

- Netflix and Yarn

Your list will not look like that. You will have your own list. But remember to find the time and space to do the things that make you happy.

*

Listen, I am not good at all of this and some weeks I am not good at any of it.

You are about to do a thing that is real and hard and that you can never be properly prepared for, not really. For the first few months, you will be more tired than you have ever been in your life. You are going to do a job that is brilliant and terrible, and that will give you unsurpassable highs and will also completely break your heart. You owe it to yourself to look after yourself while you are doing it.

And for when absolutely everything else fails, I always keep emergency ice cream in the freezer. It’s a start.